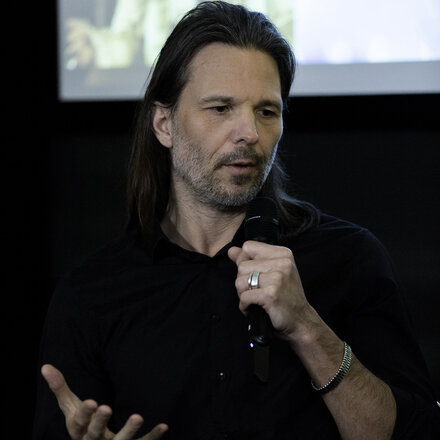

Barry Ackroyd: Interview

The veteran director of photography, acclaimed for his distinct work on films such as United 93, Green Zone and The Hurt Locker, discusses his unique approach and filmmaking philosophy.

Published on 11 October 2012

Words by Quentin Falk

Barry Ackroyd likes to describe the way he shoots as “utterly three-dimensional” – a mixture, he characterises, “of motion, light and kineticism.” Not to be confused, though, in any way with 3D; the very word makes him roar with frustration.

“I don’t want to sound like I’m from some other era; in fact, I like to think I shoot in a very modern way and, hopefully, younger DPs and technicians look at what I do and think that’s the way to go forward. Nor am I saying it as some Luddite or from a dinosaur point-of-view, but there will be no 3D films in three years time; indeed, I can’t see why people still go to watch them.

“When I watch a film I want to disappear into it and don’t want it to jump out on to my lap, or to be distracted by the technique. If a film is designed around the technique, that’s the very opposite of filmmaking to me.

“The thing I continue to love about cinema is that we hide our skills. Everyone does – from the director to the actors – inside a complete, selectively organised and built structure. The overall finished product is the object.”

At 58, Ackroyd speaks from a position of strength after a career already spanning more than 30 years. In documentary he’s worked with Nick Broomfield (The Leader, His Driver and The Driver’s Wife, Tracking Down Maggie) whilst his feature work includes several collaborations with Ken Loach and Paul Greengrass – with whom he’s most recently finished filming Captain Phillips, about the rescue of the eponymous American container ship skipper after being captured by Somali pirates in 2009.

"For me, the purpose of cinematography is not to create a single scene, but to complete the whole film on an emotional and visual level."

Ackroyd, whose recent work also includes Ralph Fiennes’ Coriolanus, Contraband and the TV pilot for HBO’s The Newsroom, is also a four-time BAFTA nominee, including for United 93, about one of the ill-fated 9/11 aircraft, and Stephen Poliakoff’s period drama, The Lost Prince, eventually winning the mask in 2010 for his astonishing, immersive work on Kathryn Bigelow’s Iraq War-set The Hurt Locker.

“The look of The Hurt Locker,” Ackroyd recalls, “somehow seemed to shock America. The way the critics wrote about it there appeared to suggest we’d come up with a new kind of realism, a new verisimilitude, that took you to a new level. Of course, it didn’t; I haven’t any illusions about that. The irony, and what they’d forgotten, is they invented that way. It came directly from the 16mm documentary world, which came out of America, from people like DA Pennebaker and Richard Leacock.

Growing up in Oldham before heading off to art school in Rochdale where an interest in sculpture would later influence his style of cinematography, Ackroyd admits that an early inspiration was Ken Loach and particularly Kes, “because I had that kind of background.” Years later, he would begin an extraordinary working relationship with the same director which has now spanned no fewer than 12 films across more than two decades, from Riff Raff toLooking For Eric.

Another Loach collaborator, cinematographer Chris Menges, is responsible, says Ackroyd, for at least a couple of pieces of enduring advice. “When I was working as a camera operator on documentaries, I remember him saying to me: ‘Forget all this chasing down corridors. The key is to put yourself in the right place and let the action come to you. You don’t have to rush around. Don’t worry because people always say things three times.’ That’s what I now always pass to operators: put yourself in the right place and let it happen.”

When asked to cite the hardest scenes to shoot, Ackroyd, newly returned from locations which included days at sea off Malta and Morocco as well as in a water tank, quite naturally names, “the whole of Captain Phillips.”

“As the majority of filming was at sea, negotiating cameras with all the physical restrictions and challenges meant capturing the story was not easy. The struggle was to connect to the subject on a human level, even in challenging circumstances. The solution is to make the camera the observer and give the film a truth.

"Any aspiring DP should watch a film like Pennebaker's Don't Look Back. Just feel the energy and freedom in that then try and make something like it."

“So when, for example, the pirates were attempting to board, and being hosed down from the ship, so we, the camera crew, were, too. When we shot in the lifeboat, we had two camera crews jammed inside being thrown around too. However, when things get tough, I can always put my eye to the eyepiece and cut out all the chaos of filmmaking.

As for scenes of which he’s proudest, Ackroyd notes: “This is difficult because I'm proud of all my work, and if I analyse it, it's the fact that I have managed to achieve what I have done by staying true to my ideas.

“For me, the purpose of cinematography is not to create a single scene, but to complete the whole film on an emotional and visual level. Most of my work in some ways has always been compromised for the overall story, allowing the film to be the star.

“If I had to choose one scene, then it would be from United 93, in the military Control room as the Twin Towers get hit. There was a combination of actors and real people, some of whom had experienced 9/11 for real.

“This combined a genuine documentary moment within the making of a feature film, which brings me to Louis Theroux [Ackroyd’s Guru pick, below] and the link from documentary to fiction, in that documentary isn't always fact, and fiction isn't always make believe.”

“In terms of visuals, I’d say to any aspiring DP that the first thing they should do is watch a film like Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back [1967 documentary about Bob Dylan’s UK tour]. Check out how that was done, just feel the energy and freedom in that then try and make something like it. That’s just the beginning of how to look at the world. Next thing is to get together with great people and make great films. The great cinematographers work with the great directors, the ones who say, ‘Give me more, make it better.’ It’s the collaboration that makes good work.”

Ackroyd’s Guru Pick – Louis Theroux: In Conversation

“The piece I liked was Louis Theroux’s. His work covers some of the subjects I worked on in documentaries, but also he sums up the link from documentary to fiction, in that documentary isn't always fact and fiction isn't always make believe. That's the road I like to travel.” Watch Louis Theroux: In Conversation