Words by Quentin Falk

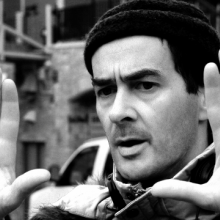

After 35 years in front of the camera – beginning at just 10 as the adorable Babyface in Bugsy Malone – perhaps the only surprise is that it has taken so long for Dexter Fletcher to make his directing debut.

In his long career from busy child and teen actor to mature performer – currently to be seen in the latest film incarnation of The Three Musketeers – Fletcher has worked with some of the finest directors: Bugsy’s Alan Parker, of course, as well as Michael Winterbottom (Jude), Derek Jarman (Caravaggio), Franklin J Schaffner (Lionheart) and David Lynch (The Elephant Man) not forgetting Mike Leigh (Topsy-Turvy), Matthew Vaughn (Layer Cake) and Guy Ritchie (Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels).

But for Fletcher, now 45, although he’d long harboured the idea of making a film himself – be it as a producer or director – it was always going to be a question of “when the time and the material was absolutely right” and, he adds, “starting modestly.”

That eureka moment was, he says, “an idea I had about a man who’s a boy and boy who’s a man.” The result is Wild Bill, a moving, sometimes comic and redemptive story, set in London’s East End during the Olympic build, of a just released, feckless ex-con (Charlie Creed-Miles) trying to reconnect with his children, including one (Will Poulter) who’s been forced to grow up way beyond his years.

“Be aware of things that you can capture in a moment – a train going past on the railway line, for example – which can later be used to give you a little respite from your story.”

Another germ was a news story he’d once read of a mother who’d gone off on holiday to Greece, leaving her children to fend for themselves. But it was also about a question of “adult responsibility” which Fetcher felt he knew only too well.

“As a child actor I had a lot of adult responsibility. It was, curiously enough, only when I became an adult actor that I realised I didn’t really know much about adult responsibilities because it was as if I’d somehow been frozen in time.

“I think it took me longer to grow up than normal, maybe because I was still trying to eke out my childhood because for so long that’s where my work still lay. So, in a sense, this was a very personal story and probably explains why I became so intense and driven to direct it myself.”

As the title suggests, Fletcher’s film definitely has a resonance with the Western genre; he admits that Once Upon A Time In The West was an inspiration, along with Robert Altman’s more quirky frontier drama, McCabe And Mrs Miller, in which, he reminds us, “you’ve got that imagery, which I really like, of a city coming up out of the ground with all the earth, mud and dirt.

“I found our locations quite early on, even while the script was being written (by Fletcher and Danny King). Once I’d found we’d overlooked the construction of the new Olympic stadium that became sort of integral to the story about Bill which was also about transformation and regeneration. It started filling in a lot of the gaps for us that dialogue or overwritten scenes might have taken away.”

“You can never work hard enough, you can never be over-prepared.”

He also cites another director, Emir Kusturica and films like Black Cat, White Cat and Underground as an influence – “There’s a genuine heart and energy in his films. They feel so real even if there’s a heightened sense to them.”

Having worked with so many fine and often distinctive directors, had that played its part, too, even subliminally, in his own transition?

“When you’re young, most of it passes you by; at the same time, the film set for me is a very natural environment and I think I was keyed a lot more into the actual filmmaking process than I first thought before we ever got started. And, of course, there’s so much you just pick up by osmosis.

“I think you are always bound to have at least one eye on jobs you might fancy and I have often enjoyed seeing how directors operate, how they tell their stories, how they use film, the framing, the composition.

“As far as asking advice from other directors for this, I decided I would try and go my own way although I worked very closely with my DoP George Richmond, a very experienced operator, and we found the ‘look’ and the feel of the film together."

What advice would he now pass on to other aspiring first-time directors?

“Something I learned really early on was to be aware of things that you can capture in a moment – the sun appearing from behind a cloud, a train going past on the railway line, for example – which can later be used to give you a little respite from your story and allow you to make a transition from one place to another.

“The other big thing is: you can never work hard enough, you can never be over-prepared. Also don’t ever be afraid to say to the people you’re working with, ‘What do you think?’ Oh yes, and make sure you always wear a pair of sensible shoes as there’s a lot of standing about.”

Fletcher was also fiercely pragmatic when it came to the scale of the film he was trying to put together.

“For me, it was always important that the script had heart and warmth and that nothing would be sugar coated or sentimental. I wanted the themes and characters to be strong, and most importantly for a first time director, whose main strength is working with actors, no big expensive set pieces.

“As a first time director I knew the huge risk people were taking financially. I was untried and untested, a complete ‘unknown’ in that sense. I knew, however, that I could bring my own friends to the party – people like Andy Serkis, Olivia Williams and Jason Flemyng – but I also had to be aware that if I started getting too big for my boots in terms of money that it would seriously reduce my chance of getting the film made. This isn’t microbudget, but then again, it isn’t exactly a multi-million pound film, either.”

“Don’t ever be afraid to say to the people you’re working with, ‘What do you think?’”

Fletcher clearly relished the actual nuts and bolts of filmmaking, especially its collaborative nature. This is perfectly illustrated in a scene of which he’s perhaps proudest, one also which he puts down “to the great skill of George Richmond.”

It begins with Bill, whiling away time in his high-rise flat, making paper planes, trying to stay out of trouble. When his younger son returns home, they begin slowly, finally to bond while launching the plane together from the window. “For me,” says Fletcher, “that scene was cinematic in its purest sense; it was a poetic way of telling the story about those characters in that particular moment. I don’t think I could ever have achieved that with dialogue.”

For him, the hardest moment was probably was trying to shoot a sex scene between two of the young actors, Will Poulter and Charlotte Spencer.

“It was very hard for all those involved. I’ve done those scenes myself, and they are never easy even at the best of times; you’re sitting in front of a bunch of hairy crew saying things like, ‘Hey guys when you kiss, do you mind using tongues?’ It feels like you’re moving into a whole different area of filmmaking,” he laughs.

Surprisingly, on that first day of shooting, Fletcher was feeling nothing but excitement. “The train was now moving and you just had to keep moving with it. I found that very engaging. It was the week before shooting I found most difficult – the nerves, the pressure. The moment, if you like, before the bubble of preparation finally burst.”