Words by Quentin Falk

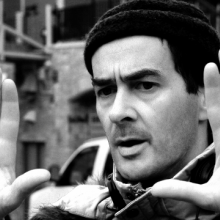

During the five years it took to make his latest film, Everyday (2012), writer/director Michael Winterbottom managed to complete not only five other full-length features but also a BAFTA-winning television series in The Trip (2010).

This extraordinary productivity, with worldwide locations ranging from Islamabad (A Mighty Heart (2007)) and Oklahoma (The Killer Inside Me (2010)) to Rajasthan (Trishna (2011)) and the eponymous Genova (2008), makes a fascinating contrast with Everyday, his first UK-set film since A Cock and Bull Story in 2005.

In his tireless tradition, Winterbottom, 51, has since gone on to complete another feature, an as-yet untitled biopic of legendary Soho porn king, Paul Raymond, starring Steve Coogan, the latest in a roll call of more than 20 films across the past two decades.

Meanwhile, Everyday tells the story of a wife Karen (Shirley Henderson) and four children separated from husband-and-father Ian (John Simm), who’s in prison for an unspecified offence.

Winterbottom’s plan from the outset was always long-term. “I went to Tessa Ross at Film Four and said we wanted to do a film about time passing across five years, to see how the children would change with the absence of the father and whether, for instance, he could maintain a relationship with them.

“At the early stage, we had pretty much a one-page story. We knew there’d be a series of prison visits, maybe one boy or perhaps a couple of kids, certainly not, as it turned out, four kids. We especially wanted to look at the way in which it might be possible to maintain some sort of loving family connection during such a long separation.

“The very idea of ‘time passing’ and how to portray it differently also fascinated me. The film I’ve just done with Steve Coogan goes from 1958 to 1992 and we’ve used all the boring conventions to convey the year we’re in. I found that quite frustrating at times.

"I've done a lot of films with a mixture of non-actors and professionals; what you do is try and create situations for them to respond to in a way that seems natural. "

“Here, we’re trying to show, in particular, the impact of time on children and instead of the normal cinema conventions we can focus on the small, subtle changes as people grow up and grow old whilst being apart.

“Everyone assumes you have to make a film in one burst, whether it’s over six or eight weeks. Why do you necessarily have to do it like that? If you’re shooting the four seasons, for instance, why not film over the course of a whole year? Why are we so lazy and conformist and think we always have to somehow squeeze it into the regulation six weeks or so?”

“Lazy” and “conformist” are certainly not applicable to Winterbottom, a eight-time BAFTA nominee whose win in 2004 for Film Not in the English Language (In This World) almost perfectly epitomises the regularly challenging nature of his subject matter.

However, the very notion of Everyday did beg several massive questions. Like having a pair of lead actors who could make a five-year commitment and, as importantly, finding a child or children that could also match the ambition of the filmmakers.

Says Winterbottom: “John and Shirley, both of whom I’ve worked with several times before, were committed from the start; they’re also friends and we somehow trusted each other to fit it all in around our various schedules. As far as the children were concerned, producer Melissa Parmenter and our casting director Wendy Brazington trawled through lots of local schools in Norfolk for suitable kids.”

Why Norfolk? “I wanted it to be in part a rural story, one that would show the contrast of the countryside with the confines of prison, especially as so often these sorts of stories tend to be urban. And,” he laughs, “I have a cottage in Norfolk so it was practical as well. We’d also filmed in Norfolk on A Cock and Bull Story and it proved to be very enjoyable up there.”

In the end, the filmmakers settled on the Kirk family and their four children, Robert, Shaun, Katrina and Stephanie and as well as using their own first names, they also used the family’s council house and the kids’ own village school as prime locations for the film, which probably took a total of 12 weeks’ shooting in all over the five years.

"I enjoy shooting films where you're not controlled by the environment. It's strange how rare that is in filmmaking."

Says Winterbottom: “No, they hadn’t acted before. I’ve done a lot of films with a mixture of non-actors and professionals and what you do is try and create situations for them to respond to in a way that seems natural. With these children, even from the very beginning, they seemed extremely responsive to the basic idea of the story and what the mood was like on set; and, in the end, maybe they did more acting than they would like to give themselves credit for.”

Asked to name the hardest kinds of scenes to shoot, he cites “those more complex technical things like trying to create different periods on public streets or attempting to marshal a crowd of 100 extras to look as though they’re enjoying themselves. Those are the aspects of filming I like least. Which is why I so enjoy shooting things like Everyday where you’re not controlled by the environment. It’s strange how rare that is in filmmaking.”

As for his proudest moment? “Someone was talking to me the other day about 24 Hour Party People (2002) and saying they had friends who were big Hacienda fans and, when they saw our film, said the scenes we shot in our fake Hacienda were just like the real thing.”

At a time and in an economic climate when many filmmakers would complain how difficult it is to generate new films, Winterbottom would seem to have a strike rate for which the word fecund seems hardly adequate.

He counters: “Look, I don’t think it’s that hard to make a film a year, which is roughly what I do. I’m reminded of the first thing I ever directed professionally which was a documentary about Ingmar Bergman. He once did two films one summer. He wrote his own scripts and also effectively produced the films as well as running the most important theatre company in Sweden where he’d probably direct three or four plays a year, too.

“Some of the best directors in history worked very prolifically; I think, for instance John Ford ended up making more than 120 films. It’s only recently that it seems to have become normal that you take two to three years to make a film. Understandable, I suppose, if you’re doing a Spider-Man or a Harry Potter where you’ve got so much to shoot. Otherwise, so much time is just spent waiting or else it becomes all about marketing.”

*Everyday is screening at the London Film Festival on 21 October. It will get a network showing on C4 next month.