Warning message

The subscription service is currently unavailable. Please try again later.Tim Hincks | Television Lecture 2015

Tim Hincks, President of Endemol Shine Group, shares his views on creativity and diversity in the television industry, and his vision for the future. Followed by a Q&A with broadcaster Steve Hewlett.

Recorded on 30 June 2015 at BAFTA 195 Piccadilly.

Transcript

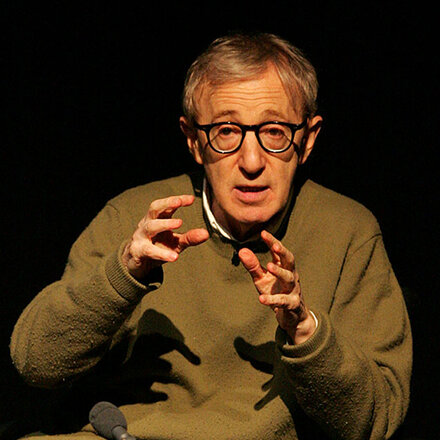

Andrew Newman: Good evening, I’m Andrew Newman, Chair of the Academy’s Television Committee, and I’m absolutely delighted to introduce our 2015 BAFTA Television speaker, Tim Hincks. As President of the Endemol Shine Group, Tim’s responsible for developing and growing the creative and strategic direction of the group which was launched in December 2014, bringing together Endemol, Shine and CORE Media. But despite such a heavyweight corporate role, Tim has remained close to the creative process and is an enthusiastic advocate of big, new ideas and innovation in television. Tim is one of British TV’s most successful and admired creative leaders. He’s ultimately responsible for some of the most successful shows across all the UK broadcasters and in all the genres: from Big Brother to Broadchurch, MasterChef to Million Pound Drop, Pointless to Peaky Blinders, Black Mirror to Bad Education, Would I Lie To You? to Wipeout, and that’s just in this country. In recent years many of Tim’s behind-the-scenes creative team, including Richard Osman and Charlie Brooker, have become big on-screen stars, and I’m half expecting that if tonight goes well, Tim will decide to follow suit.

We’re delighted that he’s accepted our invitation to deliver BAFTA’s annual lecture, which is the highlight of the Academy’s industry and public programme of TV events. In recent years we’ve had Lenny Henry, Peter Bennett-Jones and Armando Iannucci deliver this lecture, and I’ve always had a rough idea of what they’re going to say. But this evening, like a great episode of Celebrity Big Brother, I haven’t seen a script, so I don’t know what’s going to happen over the next hour. But also like a great episode of Celebrity Big Brother, I’m pretty sure it’s going to be entertaining, thought-provoking, and talked about for some time to come. After the lecture broadcaster Steve Hewlett will chair an on-stage interview with Tim and we’ll be taking questions from the floor, so do think of anything you want to ask. We’re going to be audio recording and filming the lecture for future broadcast on the BAFTA Guru website, and you will be able to find this and other highlights from the year’s programmes on there. Without further ado, please join me in welcoming our speaker tonight, Tim Hincks.

[Applause]

Tim Hincks: Thank you very, very much everyone, and thank you to Andrew for his very kind words. I mean, I knew I was good, I had my suspicions, but I didn’t know I was that good, so it’s good to have that affirmed publicly.

[laughter]

Thank you for inviting me; it’s a genuine honour to be invited by Andrew and by the BAFTA Television Committee to address you, and thank you to you for coming. You’re obviously like me, when it’s a hot, warm night you think, ‘lecture,’ so thank you very much for joining me.

[laughter]

And it’s lovely to see some familiar faces in the crowd. It’s also I’m told, I want to say a special hello, there are apparently three people in the audience who have not been bought by ITV.

[laughter]

I’m just hearing that’s now two people, so welcome to you. And I want to - over the next, you know, four to five hours - think about creativity.

And let me take you back for a second if I may to sort of, I don’t know, about 2005, something like that, and I’m in the office of the BBC1 Controller, pitching with the team a show. And let’s not go into any names of who that Controller was or might have been, and anyway, he runs ITV now so he’s gone.

[laughter]

And we’re in there, and we’re pitching, and you’re doing all the things that many of you will be familiar with, pitching the show, trying to say the right things, believing in the show. Every now and again one of the commissioning team will say, “Have you ever thought about painting the set blue,” and you say “Yep, actually, we did talk about that, brilliant that you’ve said that, can we have the commission now?” and so on.

[laughter]

So you’re thinking about how to play it right, at the same time believing in this show. And there’s even moments aren’t there when it looks like you’re going to get the commission and they’re sort of saying, “We’re pretty serious about this.” Phrases like, “We’re pretty serious about this,” and you think, don’t panic, just look like “sure you are, of course you’re serious about it, it’s a pretty good piece of content.”

[laughter]

All that’s gone on, it’s gone okay, I leave and, the… Peter, fuck it.

[laughter]

Peter Fincham has a sort of Columbo moment, and he pulls me to one side and says, I don’t think he says, “Just one more thing,” but it was kind of in effect that’s what he was saying. “Just one more thing, do you think it’s going to be any good?” And you sort of think, that’s the sort of question, I think the single question that brought Enron down.

[laughter]

It’s an apparently harmless question, but it goes to the heart of what we’re trying to do. And because Peter’s good, that’s the conversation you want to be having despite all the pitching. You want to be talking about, how does this show work, what are its flaws, how do we make it better, and have that conversation. Tonight I want to talk about that, in a way, that creativity that we’re all part of. That creative process, and how we might think about it in a different way going forward. And I want to, just be clear about it, I’m talking about creativity for the purpose of tonight across all platforms. I’m not getting obsessed about what television is or isn’t, unless you want to go on for six or seven hours, I think I’m just thinking about it across any screen, doesn’t matter what screen it’s on, I’m talking about the creative process that we’re all involved in as the world changes.

And as today’s news about BBC Three demonstrates these are, I believe, exciting times. We’re having to think about new ways of telling stories and new platforms to tell them on. So let’s not worry about the shape of it or what the platforms are. So much of what people think about when they debate about the future of our industry it seems to me is framed by the platform owners, the distributors, the consultants, the politicians. It’s no wonder they do it, they’re the ones with the most to lose, apart from consultants who are going to win whatever happens. But generally speaking, we, as creatives, as people who create content, we’ve got everything to win. And I want to talk about how in a sense we can learn from the past, and we can replicate the incredible creative explosion that has happened over the last ten years, and work out how we can be fit for purpose going forward with all the change that’s coming our way. So that’s kind of the theme, and if you don’t like that you can leave now because that’s it, I’m not changing it.

[laughter]

Now, at this point for security reasons I need to warn you, you are about three or four minutes away from a VT clip of Noel Edmonds, so you can react to that however you want. People have a number of different ways of doing it, but I think I ought to just warn you that that’s coming your way.

[laughter]

Let’s start with a question before we get into the nub of things. What might we be thinking about when we talk about creativity? What might that word mean? I think actually, and I hope you agree but I’m ploughing on whether you do or you don’t, creativity has been cheapened as a word. It’s a word that’s used so often that I’m not sure what people mean by it when they say it. In fact, creativity in our industry is a little bit like politicians when they talk about hard-working families. “It’s a policy for hard-working families.” “In which case I’m absolutely in favour.” “You’re against hard…?” “No, no, no, I’m totally into hard-working families.” It’s very much the same kind of thing. “Do we put creativity first? We definitely put creativity first. Do you?” “No, totally put creativity first. In fact, we’re trying to think if there’s a higher position than first, and if we find it we’re going to put creativity there. We’re getting dissatisfied with it being first.”

[laughter]

I believe that actually wouldn’t it be wonderful if one of the companies in our sector, indie, broadcaster said, “You know what, we’ve had a real think about this. We’ve looked at our strengths and weaknesses, we’ve looked at our track record, we’re actually putting creativity second. We think that better reflects what we can do.” But of course, not only was that funnier when I thought of it earlier - no but that’s how it works when you’re live -

[laughter]

It’s also not, to be clear, what I’m asking them to do. What I’m saying is that creativity has become something overused, and we don’t really, we’ve lost track of what it means. And I think what it doesn’t mean is, you know, skateboards to your desks. I don’t know if anyone does that. Or pool tables, or furniture or any of those things. I mean creative companies may be the sort of company, they may be a creative company where you can skateboard to your desk; I’m imagining not, I’m imagining that’s why they have skateboards to their desks.

But it’s not about that, right; it’s about something very different. And what I think it’s about is that it’s a process and a kind of craft, creativity. It’s where you create something from nothing. It’s where you create something moving, beautiful, engaging, emotional, dramatic, it’s a story. And that for my money can take place whether it’s a game show, whether it’s a drama, whether it’s a comedy. It’s about that blank sheet of paper and those few people with the real talent to turn that into something with a beginning, middle and an end, and it’s something we as an industry and in the UK have become incredibly good at. In fact we have more creatives per capita in this country than any other European country, and that is a statistic I’ve just made up, but it kind of, it sort of feels right, feels right doesn’t it?

[laughter]

So, what have I learnt about creativity, as I’m sure you’re dying to ask me. What have I learnt about that process, that process of creating something from nothing? Well firstly, it’s amazingly practical actually as a process. Yes, you want passion and you want dreams and you want real belief in what the shows and what the ideas are, but you also want persistence. You know rejection is constant in what we do. Rejection therefore has to be turned into an opportunity as well as something which is frankly deeply, deeply annoying and depressing. Because that’s what we’re up against, right? We have stories to tell and we have to persist and we have to believe in them and we have to push them. And I remember my first job with an indie called Basil Productions which was run by someone called Peter Bazalgette, who I’ve no idea what’s happened to him now but I suspect it’s not all good.

[laughter]

And he, I sat with him and said I know how to impress this guy. I said, “What we need in this company is a political panel show.” You know, I was really switched on in those days. And he said, he looked and me and said, “Right, well, you better come up with one.” And the kind of penny dropped. I thought, right, we don’t just sit here saying, yeah we’ll have a bit of that and a we’ll have a bit of this and it wants to be that, you have to create, you have to get into the craft of it. And indeed, I then took that message and I created a political panel show, which is possibly the single worst idea I’ve ever had in my life and never made it to the screen. But nonetheless, I got the message; I think I got the message. It’s about that process and about actually being practical about creativity.

Secondly, you need brilliant people. Right well we all know that, we need brilliant people, but my view is for a creative organisation to thrive, you need it to be competitive, but you also need it to be safe. Creative people are very competitive. There is nothing, and we can talk maybe later about our kind of ecosystem and how competition is so important to the creative process in this country. But you know, having a hit show is the best feeling in the world. The second best feeling in the world, let’s face it, is someone else’s show failing.

[laughter]

Come on, come on. Come on, let’s not pretend. Of course we say when someone else’s show works it’s very good for the genre, it’s reinvigorated the genre, I’m so pleased for them. But no, no, no, that’s not how we’re built, nor should we be.

[laughter]

Not just me then I’m feeling, not just me. But as well as being competitive, encouraging a competitive nature, it also needs to be a safe environment. Bringing forward an idea, a script, a thought, a concept, is the single most exposing, occasionally scary, nerve-wracking thing you can do, even amongst friends. And to create an environment where creators feel at home and nurtured is an incredibly important part of what that creative process has to be. It needs to feel safe and nurturing.

And of course finally, none of us know anything, that’s the reassuring thing. Back to that Peter conversation. We don’t know anything, alright. We go on our gut, our instinct, we go on our experience, but the joy and wonder of this industry is that we don’t know anything. And that results, all of that results in an extraordinary thing, which is that we create this content that becomes part of the national, or even at times international conversation, that sets light to Twitter, that gets social media into a rage or gets them excited. That’s the wonderful thing that we do in content and in creativity, that we create these things which are so much part of this conversation. And I wanted to give you a clip, which I have warned you about, just to demonstrate that. This is a show, it’s a little clip of a show called Deal Or No Deal, which I know instinctively just sensing the room you’re all big fans of.

[laughter]

And it’s a show that took years to sell, it got turned down everywhere, absolutely fine, around the world got turned down. It was created by a team of brilliant people who nurtured it, made it better, changed it; it was passed around different countries as we thought about how to make it work. And in my view it does exactly what I’m talking about. It’s made up of boxes that we buy from Ryman’s, right, in an old biscuit factory in Bristol, and it’s a construct that’s been created. And yet for all that, to me it has delivered some of the greatest drama on British telly. If you don’t believe me, ladies and gentlemen, I challenge you not to watch this and think about Corinne… I had to look at her name, I’m not Noel, I don’t know her that well, but she’s the contestant, as she faces a life-changing decision which may leave her very rich or very poor. I challenge you not to want to know how this ends, so please roll Noel.

[Clip from Deal or No Deal plays]

Yeah, yeah you see, yeah. You want to know don’t you? It’s not your highfalutin drama is it, but it’s, it’s extraordinary. And I’m not going to tell you, you can watch it on 4oD.

[laughter]

She loses everything. No indeed she does, it’s the 1p, so yeah, real drama.

So through a creative process we’ve created this content and these shows, in drama, in non-scripted, across the piece. We’ve built together this extraordinary industry, right, an industry built on this kind of very hard to pin down creative process. An indie sector alone worth over £3billion a year, and we’re the second largest exporter of TV content as a country in the world. So extraordinary things to be built on creativity, but tonight I’m suggesting is not a time for self-congratulation or complacency. I pause only to say, it would be wonderful wouldn’t it to be in a room where someone said, “By the way, tonight is the night for complacency.”

[laughter]

It never happens, right? So maybe slightly self-defeating, and indeed I should have kept that to myself, but let’s move on. What I’m saying is this is not the time for self-congratulation, and what I want to think about tonight is the next ten years, and how we, as I said earlier, how we learn from what we’ve done and improve on it and become more and more of a creative force with all the changes that are happening to our industry.

And I put it to you that we as an industry, having said that, have become too insular. We’re having far too many conversations with ourselves, we’re far too protective over our industry, and we’re too narrow. We’re too narrow in our thinking, and whilst that might have been alright over the last few years to have done that, we need now to open up, and if we don’t open up we’re going to lose our footing in the world, in the UK and in the world. And I want to think about how we connect. And I’ve got three themes which I’m just going to go through, three areas of how I think we as an industry can become more connected, and in that way increase our creative output and increase our talent, and create the next generation of content across any number of platforms. And the first, first area I’m going to look at in this new way of thinking about connected creativity is risk and ambition. I want us to re-think how we think about risk and ambition, and I’m going to illustrate that with a clip which we’re just going to play for you now.

[Clip of an Ed Sheeran performance plays]

So, it’s a bit like in the Big Brother house when they play music, everything goes into a little bit of a strange state. So wonderful, I love Ed Sheeran. I don’t imagine, I’m not sure whether you would be comfortable saying you do, I don’t know, but he’s certainly not cool is he? He’s not a cool brand. But I put it to you, and bear with me on this, TV needs more Ed Sheerans. This is what I mean by that, or maybe you just agree? Yeah maybe you’re happy, needs more Ed Sheerans, good, onto the next thing. It needs more Ed Sheerans. The music industry, when I look at them, are far more comfortable with mainstream content than we are in the TV industry. They’re much more comfortable with it. They take something like Ed Sheeran that I would say, Ed is… Ed, I’ve never met him.

[laughter]

Ed is an amazing piece of content, if you’ll forgive me that sort of analogy. Brilliant songs, brilliantly delivered. Maybe not to everyone’s taste, but the music industry gets behind him and pushes him, and wants as many people as possible to listen and enjoy him. What the music industry doesn’t have is kind of guilty pleasures, right? They’re equally happy with the niche and the mainstream. They’re happy with Ed Sheeran, and they’re happy with bands that I’ve probably never… Royal Blood. Any advance on Royal Blood. But you name it, niche bands. Right they do both, and they’re very comfortable with both.

And TV, I think we’re in danger of worshipping the niche. I think we’ve become obsessed with this notion of risk, and we don’t, a bit like creativity, don’t really know what it means. We all say we’ve done something risky. “Risky show, very risky show. No, no, I mean nobody watched it, but very risky. Very risky, good to have covered that area.”

[laughter]

Alright, now I am as big a fan of niche shows as anyone else, but what I’m interested in is the way that the work risk has been hijacked. And I put it to you that the mainstream is the riskiest place of all to be. And I would like to think that from tonight we can at least think about, I believe it was Grayson Perry who said, “We need to make the mainstream brilliant, and the brilliant mainstream.” I think that was Grayson Perry, I love that quote. Because that’s exactly what we are very, very good at being and have done, but that we’re beginning to lose I think a bit of focus on. Too often the popular is seen as I say as a guilty pleasure by our industry in the way that Ed Sheeran is just simply not by the music industry. Too often regulators, politicians, broadcasters and producers - very clear about that, and producers, too often they’re snobs - they’re snobbish about what we make. They’re snobbish about their own content. And I think we almost suffer when people think about our industry, certainly at that level, we suffer from what I’m calling ‘box set tourism’: people who think about our industry in terms of the box sets that they watch.

[Phone rings in the audience]

The news is just in now, I think this is going down well, what are we hearing? We’re breaking on all media. No that is embarrassing but don’t worry.

[laughter]

Too often they think about our industry through the prism of box sets, right. Now I love box sets. Endemol Shine Group makes box sets. I watch them like all of you do. But we are more as an industry than just box sets, right. The niche is going to be okay. It’s going to take hard work, it’s going to take incredible craftsmanship, it’s going to take producers, writers. As I say, the niche is a good and wonderful thing, but it’s going to be alright. All the new platforms want niche in a way that helps define them. Where everybody’s running a bit scared is the mainstream, it’s the mainstream that’s in danger. And if I can illustrate it less, no point, I don’t really want to illustrate it with science because that’s boring, I’ll illustrate it with an anecdote, obviously, because that’s how we operate in this industry, which then will prove my point.

But I want to take you to a dinner party… I don’t want to take you to a dinner party in West London, I was at a dinner party in West London and there I am sitting opposite some guy. Obviously a very smart guy, he’s an accountant or lawyer or banker, whatever, his life has gone pretty badly.

[laughter]

And he finds out, genuinely not through me, because I’m sure like you you want to keep what you do quiet for exactly the reasons I’m about to explain, he finds out that I’m involved in the television industry. And he sits opposite me and says, almost before, I don’t think he even said hello, he said, “Do you want to know what I think the worst TV show is in the world? “And I’m thinking, no, right, I really, really don’t.

[laughter]

But I nod along as you do. He said, “Well, it’s on BBC Three,” and I think, be careful what you wish for. But it’s on BBC Three, those were the days.

[laughter]

And I’m thinking without a doubt, it’s going to be one of ours, it’s definitely going to be one of ours. “Yeah, it’s BBC Three and it’s a terrible thing,” yeah, it’s going to be ours. And he says “Snog Marry Avoid” And I’m thinking, well partly I’m thinking you should have seen Help! My Dog’s As Fat As Me, but I didn’t mention that.

[laughter]

But mostly, mostly, mostly, come on, it’s a good show, it’s a good show. If we’d have put subtitles up people would have loved it, Scandinavian subtitles we’d have been fine, we didn’t think about that.

What he says is Snog Marry Avoid. I’m thinking, does he mean the show which challenges the patriarchal assumption that young women should dress in a way that over-sexualises them at an early age, and actually tries to put them back in touch with their more natural side, and helps them become more comfortable with themselves, does he mean that? It turns out he does, Snog Marry Avoid. So I think, okay, I’m going to ask him a question I’m going to regret, and I say, “What is it you don’t like about the show?” And he says, “Well I’ve never watched it.” Genuinely, and you must have had that, right? He hadn’t watched it, in which case you think, I mean I’m not going to stand before you and say, “I genuinely can’t bear 17th Century Russian literature. Awful. I mean, I’ve not read any of it but it’s terrible.” Something about television brings that out in people. And the point I’m making, we’re talking about, lest you forget, we’re talking about this idea of how we think about risk and ambition, and how we think about engaging people in the mainstream. And that dinner party conversation, rather one-way, was, I can illustrate actually, because I’m thinking, how do people think about these shows? What precisely is the nature of the danger?

Well let me put this to you: there’s a group of people as ever running Britain, running broadcasters, running regulators and so on. And I thought, well how do I have a look at this in a way that illustrates it for you? So if you want to know the answer to a question right, particularly one of national importance, we know you go to a polling company, right? I’m not wrong. That’s a topical joke about the election, where polling companies got it wrong, you remember? Yeah.

[laughter]

So, you go to a polling company, and I went to YouGov and asked them to look at a number of programmes, and put it, feed it into this survey that they do, it’s called the Opinion Former Survey. So basically the people answering this survey are you know judges and you know broadcasters, regulators, politicians etc., so newspaper editors and so on. It’s an anonymous survey, but they’re the opinion formers. And we asked them, actually I think I’ll have to press this clicker, to think about some shows and ask them what they thought about what was quality. And I think what it shows you, it’s pretty obvious right, it’s not a big surprise.

Basically, quality is very roughly speaking, the stuff that not many people watch, the box sets and so on. And by the way, let me go on record, those are in my opinion, those are all quality shows. I don’t know what Alan Yentob’s done, he’s found himself somewhere in the middle so, but Alan’s not here tonight and if we keep that amongst ourselves it’ll be fine.

[laughter]

But shows watched by millions of people are considered to be low quality, and this is a scandal [points to Snog Marry Avoid’s rating] Nought percent? Scandal. And then you’ve got your box sets and you’ve got Newsnight, and as I say, look, I believe those to be extremely high quality shows, but the point is as we’ve said, so are those. The mainstream is not considered to be quality and that’s a real issue for us. So I think, as we think going forward, we need to think, we need to rediscover our love of the mainstream, we need to rediscover our belief in the audience, our belief in what they want and what they love. And we need to get the courage, the Ed Sheeran-like courage of the record companies to get behind the content and the shows which will fail, which will fail big, but that if we don’t do that we are going to lose our way. And so it’s a very important point for me that embrace that mainstream and try and shake off the snobbery that will hold us back if we don’t watch out.

And I want to link it now to my second area, because the other way we might think about the way we approach the mainstream is in terms of talent, and in terms of how we think about the kind of people that are in our industry, and helping us create the next generation of content. So I want to think about talent now, I’ve done risk and ambition, talked about that, I want to talk about talent and how that can become more connected to the world around us, and how we need to be more connected. We’re built on talent. We’re very, very bad at bringing on talent, yeah, we just have an issue with it. And I want to show you a clip, and then I want to talk a little bit about my view of talent and how we need to get that right. Thank you.

[Clip from People Like Us plays]

[laughter]

On that bombshell, BAFTA. So that is, that’s a clip, some of you may remember that, it’s called People Like Us, it was made by the brilliant people at Dragonfly, and it was set on the Harpurhey I think, yeah Harpurhey estate in Manchester. And actually I could have shown a clip of Benefits Street too, I guess. And thinking about both of those shows, two brilliant shows, I love both of those shows, extremely well-made. I don’t buy the poverty porn debate, I think that’s overblown, hysterical, I think these are extremely well made shows. But, there’s an issue isn’t there, we get a bit exposed when it comes to shows like these. There’s a weak spot that we have that hampers the programme-makers and the broadcasters when it comes to shows like that, and it’s an industry-wide problem, it goes beyond Benefits Street and it goes beyond People Like Us and shows like that. The thing that makes us feel, I think, uncomfortable about shows like that, it’s got nothing to do with the creative intent or the quality which is remarkable, what makes us feel uncomfortable about them is that they feel like shows made by middle class people about working class people. That’s the fundamental nugget I think that makes us feel uncomfortable. And the reason that makes us feel uncomfortable is because it’s true. It’s wholly true.

I’ll just pause on that for one second. Last year Lenny Henry stood up here on this stage and kick started brilliantly the debate on diversity, and I think, you know, real traction now as a result of that, and I support that fully as I’m sure all of you do.

But coming back to that point about middle class and working class, what I think we, what I think is clear and true to me is that no measure of diversity can be truly meaningful without measuring, without a measurement of social background and social mobility. I simply believe we’re only going to get half of the way there unless we look at that and unless we measure it. Shows like the one we’ve just seen, many other shows like them, have been really, really good at inviting people from deprived, difficult social backgrounds into the edit suites, right, into the films. What we’ve manifestly failed to do is invite those people into our companies and into our creative processes and into our offices. We have just failed to do that, and it’s time to redress the balance. And I would say, if Greg Dyke was able to say that the BBC was hideously white, I would put it to you that it’s not going over-stretching this to say this industry is currently hideously middle class. And that’s an issue. That’s a big, big problem, because what I’m talking about is not moral, it’s not political, I’m talking about a talent base, right? I’m just coming back to the very basics that we need to bring as many talents into this industry as we possibly can, and we’re hampering ourselves by not fishing in a bigger pool.

Now I think it’s pretty clear why this industry might be predominantly middle class, right, it’s probably two key areas. Economics: so in particular Skillset did, as always did some great work and found that around about 50 percent of people in this industry had done work experience at some point, and that will largely be unpaid. And then the second area is kind of connections or confidence, social connections. I don’t know how you’d want to think about that, but that’s how I think about it, and that’s about sort of who you know not what you know, right, connections. 62 percent according to Skillset of people in this industry got into it via an informal interview, right, so that’s almost certainly through people they knew and through connections. Or, it’s just about being confident, right. And confidence matters a lot in this wonderful but informal industry, right, how you hold yourself, how you project yourself. And not exclusively, but that confidence and that connection is largely the preserve of the middle class, right, that’s how it works. That’s why we’re aspirational, that’s why we want to be middle class, you can buy those things.

The problem with all this is it’s probably a bit like world peace, right, you agree, I’m imagining you’re not going to disagree with this, up to this point anyway, just you wait. But the problem is it’s hard to measure, it’s hard to measure. And in some ways I actually genuinely feel up here talking about social class is a bit old Labour isn’t it, it doesn’t feel quite right, it feels like we’re all on the Aspiration Express now and talking about class as if it were a somewhat 1970s concept right, but it’s simply not true, and I think we need to address it. So let me come up with one measure that I think is a way of measuring it, a way we might look at measuring it. Because seven percent of people in this country are privately educated, seven percent. In our industry Skillset found that 20 percent of the private sector were fee-paying, privately educated, right, so seven percent goes to 20 percent. And that’s without looking at the top, right, we know that it gets, I mean anecdotally, because one of the problems is this isn’t measured, anecdotally we know that the further up you go the more that’s prevalent, right.

We did an anonymous survey at Endemol Shine Group… until tonight! No, it is still anonymous, it is still anonymous.

[laughter]

And we found that those people who considered themselves, defined themselves as senior management, 33 percent went to fee-paying schools. Now, let me be really, really clear about something. I do not have a problem with private schools, I don’t make a political point about it. Let me be frank with you, some of my best friends went to private school. It’s not their fault. My children go to private school, that’s my fault.

[laughter]

Okay, no but it’s true, I don’t have a problem with private schools at all. What I want to think about is how we fish in this bigger pool. I mean diversity, the diversity agenda isn’t anti-white, right? It’s just pro-choice, it’s pro more people having access, and this is what I want to put to you. The private school issue is about trying to stop pulling the ladder up. We pull the ladder up, right. Many of us have moved forward with our lives and become middle class in some cases, and we’ve pulled the ladder up, we’re not letting other people in, and that’s got to stop. And as I say, it’s a very complex thing to measure. You could look at schooling, you look at where you live, you could look at whether you’ve University-educated, there’s all sorts of ways of doing this.

Take my own case. I, I think, probably, and many of you will be able to say the same, probably represent how complex this issue is. I’m 100 percent comprehensively-educated, actually, I wasn’t particularly comprehensively educated, I was educated at a comprehensive. I’m a state school product, I was 100 percent state schooled. My parents didn’t go to University, but, they were a teacher and a civil servant, they were very engaged, very bright, supported me. I lived in the badlands of West Sussex; tough. No, no, no, tough, tough.

[laughter]

Our local Waitrose, genuinely, no, no, genuinely did not, I mean you’re not going to believe this actually true, look it up, did not stock organic hummus until late ’91. So we had it tough.

[laughter]

But that’s the point, it’s a complex issue. It’s one of the more complex issues in diversity but we have to tackle it. And all I would say is, new ways of measuring it won’t suddenly happen where we’ll think, I know, this is how you measure social class, it’s not going to happen, we know what the basket is, we know what’s in the mix.

And so I think we need to do a couple concrete things. One is, I believe and I propose that Project Diamond, which is I think you will probably know, which measures other, which measures diversity, tracks it with broadcasters and producers and tracks that, how we’re doing in diversity, sets targets for social diversity, right. We need to set targets, we need to agree as an industry very quickly and we need to implement them, and we need to look at how well we’re doing. And as I say, I put forward private schooling, but others may have other views, but I think we need to measure it as quickly as we can.

Secondly I think we need to absolutely change the culture of how we think about it, and I’ll just give you a parochial example before moving on. Work experience we talked about. You know at Endemol Shine Group for a while now we’ve believed that it should be two weeks work experience. You’ll remember that for others it may be longer. Ed Miliband, the Labour Party if you remember made a big issue about work experience, that in their manifesto they said four weeks work experience which would be unpaid. As so often, time and time again, Endemol Shine Group finds itself to the left of Ed Miliband on this issue, and we believe two weeks is right. But further, what we’re going to do is, we’re going to create 40, from September, new work placements, so that’s work experience placements, which no longer will just be expenses only, they’ll be paid at the London Living Wage, and in that way we’ll be able to monitor and look at who we’re attracting, and who’s coming into work experience, and hopefully remove to some extent some of the financial and economic barriers.

And on top of that we’re going to do what you might call sort of offsetting, whereby if an executive producer or producer asks a friend of a friend to come in and do work experience, absolutely fine, but we must match that with someone, always match that with someone who has come in through an unconnected route, okay, so you’re always matching it. And in that way we hope for the first time to be able to genuinely try and monitor and make something of work experience, and try and begin to break down those barriers. So I really want to suggest that we measure social class, we get to grips with it, and we stop ultimately, what the diversity debate is all about, we stop hiring in our own image. We need to move on from that. So that’s the second area, okay, of being more connected and more in the way we think about creativity, all about increasing the amount of talent we have and being fit for purpose as we go forward.

The final area, the third area where I think we need to be more connected, where I think we need to be more, less insular, is in how we think about how we think about our approach to the world, so the international scene. So a new approach if you like to our global role, and I want to illustrate that with a clip, so we’re going to show a clip now.

[Clip from The Bridge plays, but faults before the end]

Ladies and gentlemen, The Bridge. That is a genuinely, I mean it’s not Deal Or No Deal levels, but it is a genuinely, no that’s a beautiful piece of filmmaking, I don’t know if you’re familiar with The Bridge, a box set to be proud of, a wonderful piece of work. And I’m sorry you couldn’t see that because it actually genuinely brings chills to you as you watch that.

But the point about that clip there is that it came from our dear friends Filmlance in Sweden. And content now can come from anywhere, right. The world has woken up to great content. We’re fairly constantly, possibly on this stage from time to time, sort of saying in the UK we make the best, we make the best television in the world, right? We make the best content. Now we’re certainly very good at saying we make the best content in the world, but I really don’t think, I think the world has woken up, right. So content can come from anywhere. By the way, in scripted as well as non-scripted, shows coming from Spain, from Germany, from Korea, so the world has moved on. And we as an industry and as a creative industry need to be match fit, right, to compete. We need to be able to take our place.

Now let me, you know let me clear, I stand before you with a frank admission: I have been, I think you know this but it feels good to be able to tell you face to face, I have been consolidated. Endemol Shine Group have merged, you read the papers, right, merged and I’m part of a big international, global group, right, with its roots in America. Now, that means, I kind of feel the same, kind of look the same, roughly talk the same, and the shows we make and are making feel about the same, whether it’s Ripper Street, Peaky Blinders, Broadchurch, Black Mirror, see I’m giving you all the posh ones, right, it’s like at the dinner party. “Yeah, good shows.” And Snog Marry Avoid. They’re all consolidated shows, so they feel the same, look the same, so I suppose what I’m rather clumsily hinting at is that I don’t believe for a minute that consolidation, foreign ownership, or indeed size or scale means one thing or another for creativity, right, I don’t think it affects it one way or another. I think there are some brilliant big companies, I’d hope ours is one creatively, there are some terrible ones, right. There are also some brilliant small companies and some absolutely shocking ones, and let’s name them tonight. No.

[laughter]

So it’s not about scale or size, right, and it’s not about ownership in my view from a creative perspective, but I can see often people are skeptical about that, and perhaps particularly skeptical about certain types of foreign ownership. They believe that somehow it changes the culture, or necessarily changes the culture. There have even been rumours that we have as a company had to move quietly to some unknown corporate HQ now that we’re owned by different shareholders. I can’t believe I’m having to do this, but I feel embarrassed that I’m having to think about demonstrating to you that nothing has really changed, and in fact this morning I took a picture of our office building, we’re still in Shepherd’s Bush and absolutely nothing has changed. We’re still exactly the same building, there is genuinely nothing for you to see, it’s all business as usual.

[image of the Endemol building decked in American flags]

[laughter]

And by the way, didn’t the graphics department do a great job with the picket fence, don’t you think? Big round of applause, the graphics department, terrific, terrific. So, good visual gag but quite annoying to have to get the clicker.

So, so I don’t believe there’s an issue per se from a creative perspective about ownership or size, and in fact what I believe is that the UK is at its best when it engages with the world. Now I’ve been in international television and content for 15 years. I’ve been Dutch-owned for, well not personally, they literally don’t own me, actually no they do kind of own me personally, for 15 years. So I’ve never thought about it, I’m privileged to have friends and colleagues and creative colleagues around the world who I do count as friends in far flung corners of the world, that’s an immense privilege and makes me, I believe, creatively more invigorated and more excited. But above all else, and I think I speak for my colleagues as well in the UK, first and foremost I’m a UK creative and I work with UK creative teams and that’s where I come from. I mean if anything, being part of an international group maybe even gives you more of a sense of your own UK identity than otherwise. So yeah, I think foreign investment into creative companies and into independent companies and so on is a genuine boost to our economy, can be a boost to creativity, but is certainly, is certainly a sign of success, and I think we need to be comfortable with that in certain groups, we need to be comfortable with success.

So I say to you, in fact, when we’re thinking about our role in the world, beware, beware, and I’m having a run up to saying this word, beware the UKIPification of British television. Yes ladies and gentlemen, that’s what I said. I’m so confident I’m going to say it again, beware of the UKIPification of British television. Beware the little England arguments about the way our creative economy runs. Don’t turn back the clock on progress, right, on the progress we’ve made. And most specifically, help the next generation of UK creatives take on the world. And I can’t believe I’m having to talk about this because it feels to me like an ancient argument we shouldn’t have to resurrect, and it’s also a bit dull, but terms of trade, right, the terms of trade we have, are vital, in my opinion, in helping the next generation of creative entrepreneurs in this country prosper. The terms of trade work. They protect creatives, right. They fundamentally speak to an argument which I think is incontrovertibly true, which is when you create content you should be given a fair share of what you create, right, and in that way you’re inspiring and incentivising people to create the wonderful shows both big, niche, mainstream, all of them, and encourage the people to create those shows. I think the terms of trade work because they do that, and secondly, you may know this, but just worth pointing out, some independents are not included in the terms of trade, they don’t qualify, Endemol Shine Group being one of them. So this is not, I mean obviously the entire speech is about self-interest, but this is not specifically, why else do you do them?

[laughter]

This is not specifically, I’m joking of course, this is specifically about the next, in my view, generation of small, young, creative entrepreneurs who need to be backed, and we don’t want to see arguments, in my view, as I say about foreign ownership being used as a smokescreen to stop those young creatives and to set the clock back and alter the terms of trade and the terms they work in to the detriment of creativity and entrepreneurial, entrepreneurship, I think we’ll settle on that word. So that seems to me a key. So don’t stop UK creatives creating the next generation of UK content.

Ladies and gentlemen, I’m nearly at my conclusion. You look disappointed by that. Let’s remind ourselves what we’ve done, I hope. We’ve talked about the creative challenges ahead. I hope I’ve talked about it in terms of creativity rather than about platforms and which platforms are right and how they, and the sort of mechanics of it. Creativity, we are extremely good at creativity in this country, and my obsession is about making sure the next generation, on whatever screens that content appears in, are in good health and are protected and are supported. So I hope I’ve told a story of hope and optimism. I believe we are capable of great, great things together. I believe we need to be less insular as an industry. I believe we need to think about risk and ambition. I believe we need to grapple finally with this big issue of talent and social background, and I think we need to be match fit and take our place to compete with the world, and with the rest of the world. And if we do that I genuinely, genuinely believe the next ten years can be even more creatively exciting than the last ten, and I thank you very much for listening. Thank you.

[Applause]

Oh Jesus, now we’ve got to talk.

Steve Hewlett: Just relax.

TH: Okay, thanks Steve.

SH: Can you hear me? Oh good.

TH: Try and sound excited you can hear Steve, yes, it’s good news, we can hear you Steve.

SH: Thank you very much for that. That was genuinely fascinating and quite different I think to speeches of this type that have been made before. By the way, if you want to, we can play that clip now.

TH: Do you want to see the clip of Borgen? It’s lovely, yeah let’s see that. Yeah that would be lovely, yeah. It’s The Bridge, not Borgen, what am I talking about.

[Clip from The Bridge plays in full]

I actually genuinely remember where I, I just remember where I was when I was watching that, and it is a thing of great, isn’t it, it’s a thing of great, I don’t know if you watch the series but it’s an absolutely extraordinary, beautifully told show. And no, I’m glad we saw that, although I haven’t forgiven you for mucking up during the speech.

[laughter]

SH: I mean, they’ve come up with a string of them haven’t they really? The Killing, The Bridge, Borgen, I don’t know if any of you saw 1864, which I, this is a personal view, has a kind of an epic, an epic scale, and remarkably well done. What happened in Denmark, because it came out of nowhere?

TH: Well I think you’d have to ask the people behind it to be honest, and of course this is a show that came with the Shine group, right, so and Shine rather brilliantly nurtured and looked after Filmlance, and a guy called Lars Blomgren who runs that and is now overseeing our whole scripted effort around the group. But I would say Steve, the thing is, and I know why you’ve said it, but it’s interesting isn’t it when people, you’ve said there was a string of them, and people talk about it as if there is a sort of, yeah there’s a factory or there’s plan or whatever. And the honest answer is, I think if you talk to Lars who made that you know, it’s a brilliant idea, it was very hard to make, very hard to come up with. And like all of these shows you know there’s no kind of, every story is different, and I think what’s interesting about it is that it demonstrates that suddenly out of nowhere a country and an area can become kind of hot. You know we’ve seen it with Israel, for example, particularly in scripted but increasingly non-scripted. We’ve seen it obviously with UK and US, but Holland at one point, you know at one point Holland changed the world with Big Brother and shows like that and Endemol. And I think we, when we look at ourselves as creatives, we need to not, you know as I say we need to not take for granted our place in the world. Because the English language is going to be, okay it’s going to be around for some time, but actually you know there are other countries coming out with it now that are making great shows. There’s a really interesting couple of game shows now going around the world from Spain. I mean it’s, we need to up our game.

SH: One of the interesting things about, I remember interviewing one of the people who was involved in The Killing, and them saying that what Denmark really had done was they’d taken pretty well their entire drama budget, their entire fiction budget, and they’d collapsed the whole thing into this. So there was two, from lots and lots of things it was into two. So although here that looks, that’s kind of, if not niche it’s BBC Four, it’s not BBC One as it were, where it was made it was absolutely the centre of mainstream, and I wonder if that’s got something to do with it.

TH: No that’s interesting. I think, you know I think on this niche, mainstream point, you know first of all I think I’ve said enough now that I’m as, you I know I watch niche, let’s say niche programming all the time. And also, by the way, I’ve tried to do many, many mainstream shows which it turns out are actually quite niche. Didn’t know at the time, that doesn’t seem to work though when you spin it that way. Who knows what’s going to work and what doesn’t work. I mean by the way it’s true in drama, you know if you look at drama, there’s been this incredible explosion of what you might call sort of US cable dramas from the AMCs and HBOs and so on, and quite often that is brilliant, but it’s quite dark, you know quite difficult storytelling and so on, and wonderful shows, but where I think we’ve as the UK should be thinking and can be thinking is, as well as that, how do we think about the big, how do we think about coming up with the next you know Grey’s Anatomy or ER or whatever. You know how do we come up with some of the Shonda Rhimes kind of shows that are out there in drama. And indeed in non-scripted, you know…

SH: Do you think those shows are, when they begin, are they more risky?

TH: Well I think it’s more, which ones sorry?

SH: Well some of the, whether it’s The Sopranos or you know Grey’s Anatomy, are they more risky in their approach to things?

TH: Well, I think that there’s a bit of a category error that people make which is, as I say all brilliant shows, but I think what people say, what they’re thinking about when they say risk, is they’re thinking about the area that it covers, you know the story, where the story is told. In an often very difficult, challenging, it may be dark crime, it may be about child abuse, it may be some really difficult, important areas to cover. But I think that gets seen as risk, and therefore you know game shows, factual shows get seen as a big light, and actually that’s the wrong way to think about it. You know the risk of launching a big entertainment show on a Saturday night is terrifying right, and people, you know frankly people’s jobs are on the line and careers. You know, I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out Of Here!, I’ll pluck out for no particular reason even though it has nothing to do with me, but you know is a show made with real, I mean I look at that show and I think it’s made with love, it’s made with skill, it’s made with dedication, and incredible storytelling year after year after year. No one will ever talk about a show like that in public in that way, but it took a huge risk, right, these shows are very risky to pull off.

SH: So you talked about replicating the incredible creative explosion you said of the last ten years.

TH: Did I? God, I wasn’t really listening. It sounds good. I think we should do that, I think we should definitely do that.

[laughter]

SH: I think that was the phrase you used, yeah. Diagnose, can you, the success of the last ten years.

TH: Well I think, Jesus Steve. Let’s take it year by year.

[laughter]

I think there’s one fundamental thing in this, you know in this country which is this very, very important competitive landscape. So I talked earlier about how creative people are very competitive, and by the way they’re not the only people who are competitive, but creative people are definitely very competitive. And I think one of the special things about the UK is this incredible landscape, this ecology that we’ve got. And it’s underpinned, again I don’t think anyone here probably has an appetite to go into the terms of trade, least of all me very much, but is underpinned also by the terms of trade.

SH: Stand by.

TH: Good Steve, I look forward to it. It’s underpinned by the terms of trade. But it’s this really interesting environment isn’t it with public service broadcasting, commercial broadcasting and so on. And I think that ecology, there’s something about that ecology which brings out the best in people, and I think there’s something about the sort of rather, you know frankly we don’t have the resources of the US, right, so we make things on tighter budgets, we don’t have a really large, we have a pretty small base of buyers, right, there are really not that many buyers at all in the UK, and that somehow creates something, this sense of storytelling. I think we have a great tradition of storytelling, particularly through the documentary tradition and so on. So there’s a number of things which I think have led to it, and I think one of the other things, I’m very open about it, is that it’s a business, right, it’s a business what we do. And that doesn’t mean we sit there going this show’s going to make money and this show isn’t, because that’s a complete fool’s errand.

SH: Why does that change it?

TH: Well because I think that actually artists throughout the ages have been, you know it’s wonderful to work in a garret, but particularly wonderful if they’ve got a second home somewhere they can go to and relax. You know people, the commercial imperative for creativity’s quite important, and so I think being able to create a business that can look after people and support people is really important and part of it.

SH: I mean do you think then that commercially-focused or inspired or organised creative businesses are more creative than uncommercial ones.

TH: No. No, no, no, I’m merely pointing out that I think there are, you know for some people the incentives for creativity are quite important, right, quite important that you can earn from your art, right, that you can have a share in your art. I think that it’s really important to treat people fairly and that the industry treats people fairly. So I think that in the UK you’ve got this really interesting mix. And when I go, if you talk around the world, and round the Endemol and Shine Group, you know British content really does, people are really, something about it right, they listen to it, they want to know more about it. You know the BBC is very, very important in that, people are very interested in BBC content. So there’s something about the British creative, right, and the British that really, really strikes a chord, and something that we should be very, very proud of.

SH: But it kind of didn’t used to do this. I can remember well you know going to the States with formats from here and there, and the same thing would happen every time. Either they’d buy the format for the sitcom or the game show, whatever it might be they'd then sort of change it out of all recognition, it would fail, and then you’d be back to the start again. And the breakthrough moment I think was…

TH: Steve, it’s going to be okay mate. It’s alright.

SH: I’m turning rejection into something positive.

TH: I think you should have dealt with it by now is what I’m suggesting.

[laughter]

SH: Obviously I haven’t, but never mind. No, but the breakthrough moment was Millionaire, where they sort of went in and said, “Well you do it like this or you don’t do it at all.” Something changed in terms of the way that British creativity was regarded, have you any idea what it was?

TH: No.

SH: Okay.

[laughter]

TH: No, I think that, no I think there came a certain point in time when US, particularly US broadcasters thought about this much, they thought about non-scripted television as cheap filler, right. And actually what was interesting about the Millionaires and indeed the Big Brothers and so on and the Deal Or No Deals, is that that came at a time when the US networks thought, we’ll put some of this on our schedules, right, because it basically gets you from you know one drama to another. It doesn’t cost us anything. They didn’t engage with the rights, so the rights went back to the producers, and suddenly you created this incredible business. And so this is my point about creativity and commerce, not that the two necessarily have to be bedfellows, but they are at times, and there was a sort of format gold rush, right. People went to the States and started creating them, formats were created in Europe and in the UK, and that was a, you know in some senses was following that trend.

SH: Do you think there’s anything in the argument that people like the BBC might make from time to time that being commercial is all well and good, but it constrains what companies such as yours are ever really prepared to do. In other words that the tendency towards you know long-running returning series, so and so and so on, sort of is quite liable to extinguish efforts in single this, single that, single the other because commercially it just makes no sense whatsoever.

TH: Yeah, I just don’t buy that for one minute, although I recognise that argument. The very idea that we could sit there and say, right let’s bring one of our long-runners out. Let’s bring a hit show out now and pitch that. I mean we don’t know what’s going to work and what’s not going to work, right, and what I learned very early on, if you even for one second think about a piece of content or an idea or a TV idea, and think of it in terms of well this would be quite useful because we might hit our numbers this year, you’re finished, it’s over. You cannot think like that, you must not think like that. You know, you can have, you know Endemol was always a very commercial company, as was Shine, we’re a commercial company, I mean absolutely clear, I don’t think I need to tell you that. But the idea that you would sit there thinking, right, in order to hit our numbers we’ve got to do two shows like this, one long-runner, it just doesn’t happen. And it’s not how you attract and keep creative people, and I think that’s the joy of it. To me, the companies that really work are, going back to what I said earlier, are genuinely the companies that put creativity first, right, and put numbers and everything else second, right very much second. I mean it’s important you get them right, I mean of course it is, but they put them second because you cannot start from that point of view. And I think there’s another thing, I feel very, genuinely very privileged and lucky with what happened to me at Endemol and now Endemol Shine Group, is that too often I think in creative organisations, both broadcasters and producers, there seems to be this false distinction between the creative and the sort of business. And quite often big commercial, big creative operations are run by sort of business people right, and I feel very lucky that at Endemol Shine Group that’s not how we operate. Sophie Turner Laing, who is the CEO of Endemol Shine Group, is a content person from beginning to end, and that’s also where I’m from. And there isn’t this sense of well the business is here and creativity is here. It’s all one thing, creativity is everything. And you make a big, big mistake if you try, if you think that creativity is a way to pay the bills because it just isn’t, as long as you think about it.

SH: But when Endemol was privately owned as it were, I can see how that might be one thing. Once venture capital comes in and big owners from abroad, and it becomes in its previous, last but one existence as it were, did nothing change? I mean did they not, they must have started demanding the numbers. I can’t imagine being owned by a corporate or a VC or whoever who doesn’t at some point start demanding the numbers. However you worked before, it must have changed some things surely?

TH: I think that what you have to do, and I think that good management in companies like this have to, there has to be a process of discussion and education frankly, right. When people come into the content business as investors and so on, you might find yourself in a situation where you’re having to have the sort of situation you and I are having which is to say, “Look, here’s a show…“ - sorry, I’m not pretending we live in some kind of hippy wonderland where no one talks about the figures, what I’m suggesting is that we might say that here’s a show, I mean this will be familiar to any indie, whatever size - “this is a show that we think might be, going to be big in six countries, in which case it might be worth this,” but it’s very important to state that it might be, right. It might be worth that, it might not be. It might be worth nothing. And I think it’s how you manage that process.

SH: But do you not find yourself, do you not begin to find yourself driven to sort of favour things which you know rather more than might be, where your instincts tell you that it’s liable to produce the best commercial return. Is there a category of programme which might not be brilliant but is a great international seller?

TH: Right so, there’s some really interesting stuff in what you said there Steve because I think it sort of goes to the heart of what I’m trying to talk about. Which is you know kind of, firstly, I don’t believe in this distinction between sort of there’s some brilliant programmes and you know there’s some commercial ones. It’s just not true. People here will be familiar with this, and Endemol Shine is no different. We are a collection of creative people. Without the creative people it’s over, it’s finished, it’s literally, it’s gone, right. So we’re in a constant daily battle, right, to create, to tell the stories we want to tell, to push those stories forward. You can’t possibly sit down, I can’t sit down with any number of creatives with a scripted or non-scripted and have a conversation with them and say, “Could you just make that a bit more commercial. I love it, but a bit more commercial.” I mean what on Earth, I mean I just cannot imagine how you would have that - it would be quite fun to try - how you’d have that conversation, that doesn’t happen. So I think there isn’t a category of sort of the commercial ones and the cool ones or however you want to put it. Secondly, I think that actually my experience in the past has been that when you have you know private equity and those sorts of people involved, you know frankly you try and stop them talking about the shows. That’s all they want to talk about. Because there are great shows, right, people like the business we’re in, it’s a privilege to be in our business, and I’ve genuinely not found any issues along those lines.

SH: And how do you find the culture of the company that you now inhabit, because clearly that’s a pretty big change. So Endemol had its particular culture, then the VCs and the investors get involved. Shine was a different sort of company built largely on acquisition I think it’s fair to say, that doesn’t mean it was uncreative in the general sense of the word, there were some good people in there, of course there were, and it became you know very successful. But you’re putting together two companies that have quite different, well, tell me, what’s it, how would you characterise the cultures or both companies, and how have they gone together?

TH: I would say quite simply that the reason that the company, Endemol Shine Group, has gelled so quickly in such a short space of time is exactly the reason I said, which is they are basically a collection of incredibly gifted creative people, right. Talented, creative people who are all trying to do one thing which is to tell their stories, right, tell their stories on any number of different platforms and in countries throughout the world. And I think the secret to that is genuinely being you know open with creative people, understanding where they come from, where they want to get to, and also believing as I do that there’s a thousand cultures. I mean the culture of Endemol Shine Germany is probably a bit different from the culture of Endemol Shine Holland, US, and the culture in the comedy department of Endemol Shine Germany - yes, there is one - is probably very different from the Endemol Shine Germany factual. I mean it’s a thousand flowers bloom, but I think that’s really important because that’s, otherwise people wouldn’t be there, and we wouldn’t be making the sorts of shows we’re making. It’s very important that that creative culture which is about letting people be who they are, and honestly pursue their dreams. I mean I really believe that we’re in this business because for whatever reason we have this desire to tell stories. I mean I always think of myself as a rather thin-skinned person, so I still can’t quite work out why I’m in an industry where you’re constantly judged and you put your shows out there, and Twitter tells you it’s shit all the time and all the rest of it. Somehow we do that, and that’s who I’m in business with if I can put it that way.

SH: It’s a psychological flaw.

TH: it’s a deep psychological flaw Steve, yeah. It’s a real problem.

SH: We share it, except that you’re more successful than I am.

TH: Well I didn’t want to say that, but…

SH: No, it’s true.

TH: I think that’s what people are thinking.

[laughter]

SH: So in terms of the broadcasters, Kevin Spacey you know famously when he made his Edinburgh speech…

TH: He runs ITV studios does he? Oh no, that’s Kevin Lygo, sorry.

SH: Kevin something, anyway. Kevin made the point at Edinburgh when he said that, he talked about the liberation of doing his series through Netflix. You know he talked about the suits rather disparagingly, he’s talked about network people and how, what a liberation it was not to have network people around him. You’ve talked about creativity from the producer’s standpoint, what’s your view of the contribution that TV networks and network people and commissioners these days make to it?

TH: I genuinely have always seen the business we’re in as a business, given that as I said earlier that we know very little about what’s going to work and what’s not going to work, it’s all about partnerships, it always has been. It’s about holding hands with the broadcaster for example and being, you know I’ve never been one of those people, and I don’t think you know people I work with, where we just believe we’re always right, and actually the broadcaster is the enemy and they’re getting everything wrong, and when they decommission our show we send them whole files to show, no, but the audience figures are actually this. You think no, I think they’re probably onto the audience figures, I think that’s probably what they do. So I don’t, I mean I don’t have this, I never have this issue about oh the broadcaster said this, that or the other, I mean I genuinely don’t, and I don’t think that’s a healthy way to be, and I think we’re all trying to work together, right, on how we make these shows. So I think it’s, you know I think if you’re Kevin Spacey it’s probably relatively easy to take that view, but I think even if I were, if you can make this leap, if I turn into Kevin Spacey I still think I’d be collaborative. I think collaboration is at the heart of what we do in creativity, and that goes for within a company as well as with broadcasters and clients you know.

SH: What do you think about the BBC’s decision today on BBC Three?

TH: I think it’s a really proper opportunityfor us is what I think. I think that, let’s, I’m not going to sort of get worried if you like about how we got there, how the decision was taken, and I’m certainly not going to question the genuine, heartfelt campaign that has been fought and indeed I’m sure will continue to be fought by colleagues and friends and people that I admire. But honestly, I sit back and I think, the future isn’t coming, the future is here, and we need to learn to tell those stories and engage with a young audience who are increasingly disengaging with traditional means of distribution in television…

SH: But have they disengaged to the point where you simply don’t need a channel?

TH: Well as I say, I’m not into how they got there or you know what the sort of, how the maths add up or so on, I’m merely saying that I think this is now an opportunity for us. See I think we need to go back to what makes - and forgive me for talking about the indie sector but you know any members of the creative sector - but we need to go back to what made the fundamentals of the indie sector: creativity and entrepreneurialism, right, imagination, looking at sort of problems and getting round them, and putting content first. And I think this is now an opportunity to engage with the BBC properly and say, okay, this is now what’s happening, let’s engage now and make sure that what’s happening as BBC Three moves online, let’s make sure we really are engaging with that young audience, and let’s work together to make it happen, right. That’s an opportunity for us, and it’s where we’re all going. And if I look around the world and think about the people I work with around the group, the idea of an amazing broadcaster like the BBC, publicly funder public service broadcaster, helping us right to talk to the key audience who are becoming disengaged from television, to help us to work together to help us do that I think is an incredible opportunity. And I hope that what it does is, as we have this conversation, as we try and make it work with the BBC, and I mean I’ve no doubt there will be issues, right, and there will be discussions and arguments, but what we bear in mind is the next generation of UK creatives, and that this becomes a real opportunity for them.

SH: Lastly from me, and do be thinking of questions, contributions, things you’d like to say because we’ll get there in just a second. You talked about consolidation and foreign ownership as being in your experience sort of at worse of no consequence and actually rather better than that I think, but they had improved things in your view. Do you think, do you really think that the points made by David Abraham, Tony Hall, you know Tony Hall says is it right that independent producers that are part of global media organisations, bigger than the BBC, need guarantees or special negotiating protection? David Abraham said lots of things like Channel 5 now takes orders from Viacom in New York, Liberty and other US shareholders are playing footsie with ITV, Dr. John Malone owns Virgin, All3 and Discovery, indies nurtured over decades snapped up almost wholesale, acquired by global networks and sold by private equity, etc., etc. Percentage of UK production that qualifies as independent has gone from 76 percent to 50 percent, he says the super indie has in effect become redundant, there are indies or studios. Is there nothing at all in the arguments they make about the downside of consolidation?

TH: Well, I think I made it clear, I don’t think, we’re not asking for any special pleading, right. I mean again on the terms of trade it’s quite clear, right, we’re a non-qualifying indie, so that’s where it is. I don’t buy the arguments that it’s, no, I mean I believe that we’re a, you know Endemol Shine in the UK is a company full of UK creatives making shows for a UK audience, employing UK people and operatives. I mean no, and as I say, I suppose I’m relaxed about it because I’ve been part of an international group for 15 years, right. Other people, I mean people in the audience might be less relaxed, but I feel relaxed about it because I think in the end it’s UK, ultimately you know, there’s no such thing as making a global, you don’t make a global piece of content, right, what you do is you make a local piece of content, right. Everything we’re doing is focused, in the country is focused on serving the British, right, the UK audience, right. We don’t start thinking, well if we’ve created this maybe it will also work in America. No, we have to do that first, and that’s the sort of the failsafe.

SH: And presumably if you didn’t they’d decommission it?

TH: Yeah I mean, well as I say, you have to serve the audience, and the increasing trend now over time will be about talking far more directly to the audience than we ever did before, which is why I made my mainstream point. And also by the way, because we’ve forgotten it, why I made the point about class, because I think that’s far more frankly important an issue about how we think about, how we think about widening our circle, widening our gene pool. Because there’s a really big challenge coming which is engaging with the audience now in ways that are unmediated, right, especially when you think about the digital space. And so we need as many people coming into this industry and being attracted to this industry as possible. I think consolidation is a sign of this.

SH: And you don’t think there’s anything in the argument that the balance of power if you like between the broadcasters and the producers is changing when it comes to dealing with companies like yours, in what they would clearly regard as an unhealthy way, that the balance of spoils, that the British TV’s ability, David Abraham would say this I think if he was here, the British TV’s ability, Channel 4’s ability to invest in you know new talent, new ideas, new content and so on, is at risk in the future if they don’t get a bigger share of the returns from the things which make it?

TH: Well, there are hardly any buyers in this market. I mean that’s a bit of a subjective thing to say but what, there’s still four buyers right, so it’s you know…

SH: Possibly five.

TH: Okay, five buyers, I’ll give you that.

SH: Six.

TH: But you know it’s a very small, right, it’s a very small playground that we’re in, right, so we should remind ourselves of that. And there are any number of players in there. I believe, you can call me naive but I believe a good idea is a good idea wherever it comes from. I believe that people commission ideas because they’re good and not because they come from a particular company. And I think as I said before, you know the way we operate here with the terms of trade and so on, that’s really good for small producers. You know when I look at ITV, we can look at ITV Studios, by the way I have no problem with what ITV Studios are doing by the way, I’m sure they’re doing the right thing, but ITV Studios is, and BBC Studios make Endemol Shine in the UK look like a pinprick.

SH: And have you never been tempted, and in fact said to a broadcaster, “Okay, you can have this, but I’ll only give you this if you take this.”

TH: I should take you pitching with me Steve, you’re pretty impressive.

SH: Well, I mean that’s the other point, the only other leg of this argument that I can see might have something in it, but I’ve never been in the room when it’s happened, is that you have significant leverage because you have scale and you end up with shows which they kill to get.

TH: No, right, but exactly. I think there are times when as a producer you might have a really interesting piece of content, right, a hit piece of content. It could be in drama, could be in entertainment, where indeed you probably have you know to be frank, a little bit more power to get the right cost for it, you know if you want to do it in a certain studio you can probably get that, if you want to film it in a certain location they’ll let you because you’ve got leverage. But Steve, that has precisely nothing to do with the size of the company or whether who owns it or not. That’s to do with a piece of content, that could be a very small company who’ve had a breakout hit, or it could be a very big company, it’s about the content, that’s the point for me.

SH: Okay. Who would like to come in and ask a question? I can’t really see, but there’s someone in the middle here. Do indicate and I’ll get to you. Chap here, and who else would like to, someone over here. Do tell us who you are when you get the microphone.

Q: My name’s Rajan, hi Tim, I work for the BBC. I want to delve a bit deeper into this notion of social mobility which you touched on. I just want to know in a sense, and let me be perhaps a bit provocative here, but I think what you talked about with work experience, stuff like that is possibly just tinkering at the edges. What we’re talking about here is social mobility in the media has got worse, I mean there are surveys about this, just as with race and diversity in that sense. Ultimately social mobility means not only people going up but certain people coming down, and that means possibly the people who overfill the top echelons, the managerial echelons of TV who perhaps are all possibly white, middle-aged, private school educated or whatever, have to sacrifice in a sense their places in order for that gene pool which you want to widen, in order for that to happen. I mean can you see a radical way in a sense of doing this, of actually making this happen?