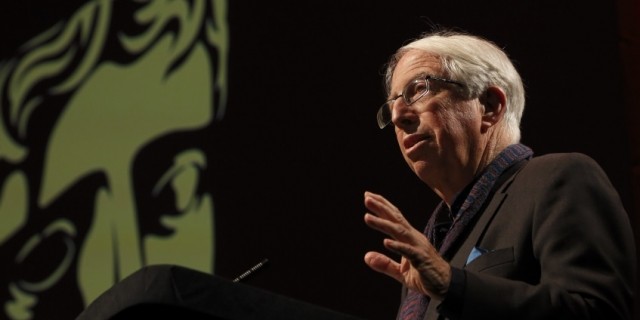

Roger Graef: A Manifesto For Filmmakers & Commissioners

In recognition of Roger Graef’s groundbreaking contribution to the British film & TV industry, BAFTA hosted a tribute evening, in which Graef offered his views on the evolving landscape of documentary production.

Published 13 May 2014

Words by Emma Reidy

On 12 May 2014, BAFTA held a tribute evening to celebrate Roger Graef’s 50th year as a filmmaker. During the event Graef looked back over his career in conversation with BBC One controller Charlotte Moore and outlined a 12 point manifesto that “will help filmmakers and commissioners build on the current success of documentaries.”

"Time is key to protecting our work."

Graef began his speech by outlining the significance of documentaries in comparison to the cyclical nature of news reports and the legacy that documentary has the capacity to achieve. He noted that “we need time to check our sources” and the traditional journalistic approach of meeting deadlines and breaking stories should not be considered more important than conveying the truth.

"We need more foreign stories in documentaries, not just about countries in extremis."

This led Graef to discuss misrepresentation of foreign stories in documentaries, and how the resistance to commission documentaries about foreign countries “feeds the ignorance of diplomats and politicians and journalists about countries like Iraq, Ukraine and Afghanistan with what we all know are disastrous consequences.”

"Loosen control of commissioning from the top."

The lack of freedom to explore stories, foreign or British, comes down to the fact that they are considered a risk by commissioners, which according to Graef is the root of the problem.

"Commissioners need the time and the freedom to take more risks."

He argued that the expectation to produce an “editorial specification that obliges us to predict our film’s content in detail before we even start shooting” is a fruitless activity, limiting the possibilities upon which exciting documentaries rely. Documentary makers and commissioners must be free to respond to the changing circumstances that real life events often produce, creating a need for the freedom and time to take risks.

"Don't try to predict the ratings."

Graef spoke of the difficulties of predicting viewer ratings and the paradoxical discord of commissioning “originality, distinctiveness, surprise and impact, which the best documentaries provide”, whilst demanding proof that an observational film will be a commercial success before it’s been made.

"Find characters that viewers will care about."

The matter of subject was explored in detail in Graef's manifesto, which suggested that good documentaries are “story and character driven, and we need to mind about what happens to the characters in our films.” He urged the documentary makers of the future to “find the characters that viewers will care about”, without forgetting the ordinary men and women that have captivated the British public in the past.

"Try new talent, both in front of the camera and behind it."

Graef also offered some practical advice for filmmakers, urging them to nurture new talent and give newcomers in the industry the opportunity to get their work seen.

"Let subjects speak for themselves."

His manifesto warned filmmakers against “telling viewers what to think.” Graef also suggested an avoidance of the ‘Voice of God’ narration, explaining that in the best documentaries “you hear the largely unmediated voices of the people in the films.”

"Make room for failure."

Reflecting on when things have gone wrong in his career, he advised aspiring documentary makers to embrace defeat, as "often the best ideas emerge from dead ends or wrong turnings or failed efforts." Acknowledging that this was easier said than done, Graef put the onus on channels, who "need to be seen to support bolder commissions" so that the struggles against ratings and a crowded market do not impact negatively on the quality of the content.

"Think about what you're doing and keep track."

Digital filmmaking has opened up a world of possibility for documentaries, because as Graef explained, you can shoot hours of material and it doesn’t cost anything. Whilst this can be valuable, he pointed out that “editors get drowned in material. And directors often have too little time to view all their rushes”, so it is worthwhile considering in detail the footage being captured during filming.

"Trust your material & trust the viewers."

Ultimately though, Graef concluded that good documentaries rely on trust. Commissioners must “trust the filmmakers to find good people as they immerse themselves in the story”; whilst filmmakers themselves must trust their material and trust an audience to “come out in their millions for important films on important subjects.”