Words by Jamie Russell

Back in 2004, Steven Spielberg famously remarked that we’d know that video games had matured as a storytelling art when they “made us cry on level 17.” For many at the time, it seemed like an impossible dream. Video games as a medium were never originally designed to tell stories. The earliest games came with more instructions than narrative (“Avoid missing ball for high score,” was Pong’s pithy attempt at context), but as technology evolved the medium did too. Only 38 years separate Pong from this year’s BAFTA-winning “interactive drama” Heavy Rain. Yet in technological and artistic terms it’s like comparing the 16,000 year-old Palaeolithic cave paintings at Lascaux with, say, The Bourne Supremacy.

Today’s blockbuster games can’t escape our desire to play within the stories they tell. Video games are still in their infancy as a form (after its first 40 years, remember, cinema had just got to grips with sound) but they already know what makes them different from novels or movies or comics: their interactivity. “Games aren’t about story first,” THQ’s Danny Bilson recently said as the company released its first person shooterHomefront. “They’re about interactive experience – the story is there to make you care about the mechanics, to make it more emotional.”

"Can games tell stories that are about more subtle emotions than just an adrenalin rush?"

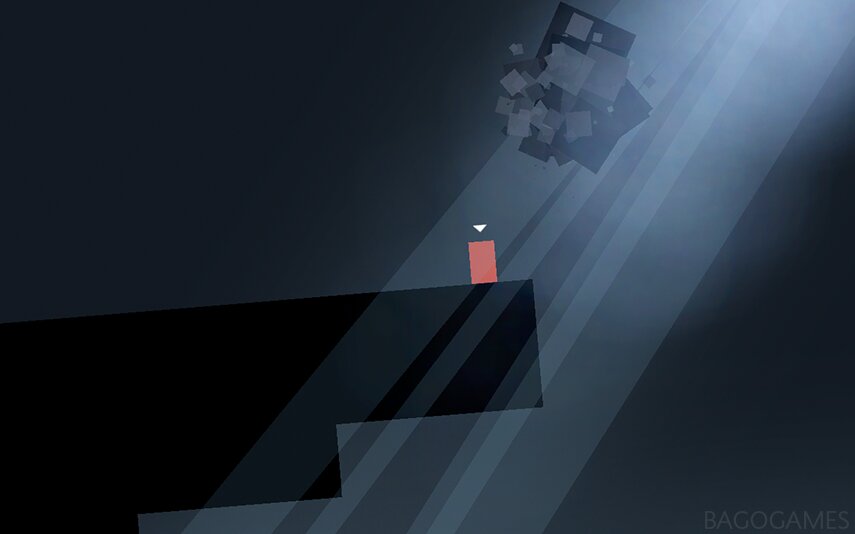

There’s no one way to tell stories in an interactive medium: a title like Call Of Duty: Black Ops might use its epic, Hollywood blockbuster storyline as a shell for its shoot-run-jump mechanics. A horror game like Alan Wake uses pages from its novelist protagonist’s latest work to propel the narrative onwards. An indie puzzle-platform game like LIMBO combines a minimalist plot and shadow puppet characters with an aesthetic brief inspired by German Expressionist cinema. What unites such disparate outings is their interactivity: you don’t passively watch these stories; you play in them.

Developers are still experimenting with the limits and scope of the medium. At the same time as photorealism and motion capture are allowing greater fidelity to reality, storytelling is being pushed to its limits. Grand Theft Auto IV balances out a sophisticated cut-scene storyline about immigrants discovering the lie of the American Dream with emergent gameplay that let players tell their own stories in its open world. “Controlling a character in a world,” Rockstar’s Dan Houser has said, “makes you feel like the star of a movie or TV show.”

Luring novelists and screenwriters into their sphere, video games are coming of age as a storytelling medium. French developer Quantic Dream’s Heavy Rain suggests the potential. Can games tell stories that are about more subtle emotions than just an adrenalin rush? Quantic Dream boss David Cage thinks so. Asking players to brush their character’s teeth, play with their virtual children and drink orange juice,Heavy Rain pioneers a certain kind of interactive storytelling. “The moment you feel you're in the character’s shoes,” Cage says, “you’re going to share what they feel.” Cage has proved that the simple mechanic of fixing a microwave meal for your estranged, virtual son can be the basis for a different kind of video game story. Soon we’ll be blubbing long before level 17.